THE STAR

OF BETHLEHEM I:

Astronomical

Perspectives[1]

This article is the first of two parts, covering astronomical phenomena leading up to the birth of Christ. In the next issue, we shall look at historical matters concerning the birth of Christ.

The usual planetarium presentations

about the Star of Bethlehem will present comets or novae (exploding stars) as

possible candidates for the Star of Bethlehem.

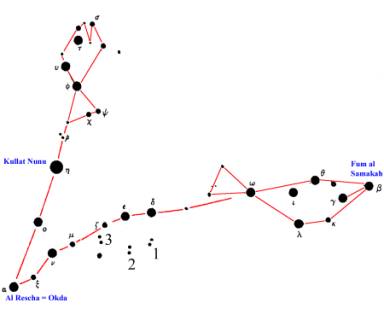

Most of them will end with the triple conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn

in Pisces in 7 B.C. (Figure 1), which the astronomer Kepler introduced as the

Star of Bethlehem. The planetarium

presentation will generally end by confidently proclaiming that the birth of Jesus

was in March of 4 B.C. or perhaps even as early as 7 B.C.

The usual planetarium presentations

about the Star of Bethlehem will present comets or novae (exploding stars) as

possible candidates for the Star of Bethlehem.

Most of them will end with the triple conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn

in Pisces in 7 B.C. (Figure 1), which the astronomer Kepler introduced as the

Star of Bethlehem. The planetarium

presentation will generally end by confidently proclaiming that the birth of Jesus

was in March of 4 B.C. or perhaps even as early as 7 B.C.

Figure 1: The triple

conjunction of Jupiter (upper) and Saturn (lower) of 7 B.C. In the first conjunction, on May 27, the two

objects were 0.99 degrees apart. The

second happened on 5 October at 0.98-degree separation. The third happened on 5 December at a

separation of 1.05 degrees. At no point

did the two planets appear less than two full-moon diameters apart.

However exciting the events presented by the planetariums at Christmas time may be, they pale in comparison to the astronomical events that took place during a 20-month period from May 3 B.C. to January 1 B.C. This was one of, if not the most remarkable series of celestial events since creation. At the time, these celestial events inspired many wonderful interpretations by the priests, astrologers, and politicians of the time. Moreover, the celestial pageantry occurred when the entire Roman Empire was in celebration. To Rome and to Augustus Caesar, it was as though the heavens were confirming their greatness. But after a year of euphoria, a visit of several wise men to Jerusalem—seeking audience with whom they knew would be the greatest king ever—doused the euphoria and replaced it with a paranoia that would drive kings and emperors mad for millennia to come.

The Heavens Declare

On May 19, 3 B.C., the planets Saturn and Mercury were in close conjunction in Taurus, passing within 40' (the ' denotes minutes of arc) of each other. (For comparison, the diameter of the full moon is 30' of arc.) Next, Saturn moved eastward through the club of the constellation Orion to meet with Venus on June 12, 3 B.C. During this conjunction, the two were only 7'.2 apart.

As if those events were not enough, on August 12, 3 B.C., Jupiter and Venus came into close conjunction just before sunrise, coming within 4'.2 of each other as viewed from earth, and appearing as a very bright morning star. This conjunction took place in the constellation Cancer. Ten months later, on June 17, 2 B.C., Venus and Jupiter joined again, this time in the constellation Leo. The two planets were at best 6" (seconds of arc) apart; some calculations indicate that they actually overlapped each other. This conjunction occurred during the evening and would have appeared as one very bright star.

The constellation Leo was thought to be ruled by the sun, the “chief” star of the heavens. It was considered the “Royal Constellation,” dominated by the star Regulus. The name Regulus itself is derived from the Latin word for king; Regulus was considered the “King Star.” Leo was thought to bestow royalty and power for any of the planets found within it. Jupiter was regarded by the Romans as the guardian and ruler of the Roman Empire and it was thought to determine the course of all human affairs. Venus, then in conjunction with Jupiter, was claimed to be the mother of the family of Augustus. So here were the two planets dedicated to the origins of Rome and the sovereignty of Augustus merging together in a “marriage” during one of the most glorious years in the history of Rome—the silver jubilee of Caesar Augustus’ undisputed reign—and in the constellation of Leo, at that.

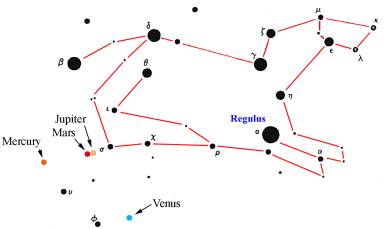

Figure

2: The

constellation of Leo, the lion, showing the locations of all the known planets

there near the end of the celestial pageantry leading up to the Lord’s

birth. The date is 27 August of 2

B.C. The sun has just entered

Virgo.

Figure

2: The

constellation of Leo, the lion, showing the locations of all the known planets

there near the end of the celestial pageantry leading up to the Lord’s

birth. The date is 27 August of 2

B.C. The sun has just entered

Virgo.

That this conjunction occurred during a full moon was also important to the Romans. Full-moon day was especially sacred to Jupiter, and the day itself was called “the Trust of Jupiter.” It was celebrated as a time when faith and trust were supposed to be given to the guardian and ruler of the Empire of Rome, whether human or divine (and in the case of Augustus, there was little distinction).

Still another rare astronomical event occurred 72 days after the conjunction of Jupiter and Venus, on August 27, 2 B.C. This was a close grouping, a massing, of the planets Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury (Figure 2). It also occurred in the constellation Leo and during the month of August when most of the Roman festivities for that unusual year were taking place. This was interpreted by astrologers as “common agreement of purpose.” It was seen to herald a new and powerful beginning for Rome and the rest of the known civilized world.

The King Star Assents

On 12 August 3 B.C., just 33 days after the Jupiter/Venus “morning star” conjunction, Jupiter came to within 19'.8 of Regulus. Regulus is the chief star in Leo, lying practically in the path of the Sun, and was therefore afforded the additional epithet of “Royal Star.” Here was the “King planet” now encountering the “King Star,” and in the Royal Constellation at that. If viewed in isolation to other astronomical occurrences this single event might not have been significant to star gazers, but combined with the other celestial displays of 3 to 2 B.C., it soon took on increased symbolic meaning. This is because the conjunction was the first of three meetings of Jupiter and Regulus. After Jupiter’s first close pass with Regulus, Jupiter continued on its normal journey through the heavens. On 1 December 3 B.C., Jupiter stopped its motion through the fixed stars and began its annual “retrograde” motion. In doing so, it once again headed toward Regulus. Then on 17 February 2 B.C., the two were reunited, 51' apart. Jupiter continued its retrograde motion another 40 days and then reverted to its normal motion through the stars. Remarkably, this movement once again placed Jupiter into a third conjunction with Regulus on 8 May 2 B.C., 43'.2 apart.

As a sign, it appeared as though the King Planet was circling over and around Regulus, the King Star, “homing in” on it and pointing out the significance of the King Star as it related to the King Planet. This circular movement of Jupiter about Regulus would probably have signaled that a great king was then destined to appear. This circling motion also provided another significant astrological observation. The zero line for beginning and ending the 360 degrees of the Zodiac was thought by some astrologers to be located between Cancer and Leo. (That is roughly where the Vernal Equinox would have been at the creation in 4000 B.C.) This meant that the easternmost edge of Jupiter’s circle about Regulus lay just touching the origin the astrologers of the time used for astrological measurements. It lay at the starting section of Rome’s zodiac.

This interpretation is different from that which may have been designed by Moses. Since the Hebrew year designated at the Exodus started at the Vernal Equinox (first day of spring), the Hebrew zodiac began with the sign of Taurus. At the time of the Exodus (circa 1500 B.C.), the Vernal Equinox was in Taurus. The association of Leo with the tribe of Judah arose from Genesis 49:9-10.[2] Whatever the case, these indications would unquestionably have shown the people of that era that a great king or ruler was then being introduced to the people of the world.

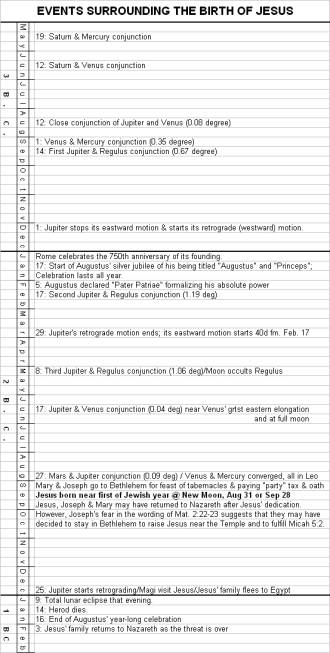

Table I: The astronomical events surrounding the birth of Jesus

Heralding the Greatest Man in the World

And who was the greatest ruler then in existence? The average man would have answered, “Caesar Augustus.” Now these celestial events coincided with the silver anniversary of Caesar’s gain of the titles “Augustus” (Reverend) and the Princeps (Leader) signifying his elevation to supreme power over the Romans. 2 B.C. was also the 750th anniversary of the founding of Rome. That same year the people and Senate of Rome bestowed upon Augustus his supreme title of Pater Patriae (Father of the Empire). To those in Rome, it seemed as though heaven itself was giving approval both of the emperorship of Augustus and Rome’s divine right to world sovereignty. Hardly a person in Rome would have disputed this interpretation and most people would have agreed that the astronomical evidence in support of this interpretation was overwhelming.

In other parts of the world, however, these astonishing celestial events were interpreted in a different way. The Magi from Persia in the eastern world were also watching the same celestial phenomena and they reached a different conclusion. They interpreted the signs as heralding the advent of royalty; not in Rome, but in Israel. The influence of Daniel on the Magi is readily apparent in both Scripture and history. From Daniel’s chronology and a study of the Old Testament, the Magi could have computed the approximate date of the King’s birth. They also knew that this was no ordinary ruler but the “stone cut out without hands” (Daniel 2:34). To the Magi, the greatest man in the world was not to be found in Rome and its festivities. The wise men headed toward Jerusalem in Judea, expecting to find a special child whom they considered to be born “King of the Jews.” To the wise men, the greatest man in the world was a young child named Jesus.

The Nature of the Star

Having seen the celestial pageantry leading up to the birth of Jesus, we now come to the matter of the star itself.

Because of Jupiter’s behavior in the time leading up to Jesus’ birth, many have concluded that Jupiter was the Star of Bethlehem. The problem with that interpretation is that Scripture records that the “star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was” (Matthew 2:9). The daily motion of a planet such as Jupiter is like the motion of the sun and stars in their daily motion, namely east to west. But the wise men were traveling north to south from Jerusalem. How, then, can the Scripture say that the star “went before them”? To do that, the star, too, must have moved north to south.

Still, most commentators today favor the “King Planet,” Jupiter, as the prime candidate for the Star of Bethlehem. Identifying Jesus with Jupiter in this way suggests that Scripture, too, should relate Jesus to Jupiter. Scripture, however, says in Revelation 22:16 that Jesus is “the bright and morning star.” The morning star is Venus,[3] not Jupiter. So it is unlikely that the star is Jupiter.

A minority of expositors claims that Saturn or one of the other planets, even faint Uranus, was the Star of Bethlehem. Astronomers generally claim that the Star of Bethlehem was a nova or a comet. Despite all the pageantry and claims, there is no satisfactory explanation as to how any of those objects could direct the wise men to a specific house in Bethlehem.

Some scholars assert that the star was only visible to the Magi, that it went before them during their journey to Jerusalem and finally led them to Bethlehem. This claim is misleading, but not entirely false. The stars and planets were there for all to see, but it took the training of the Magi to understand the significance of their movements. It is clear from the wording of Matthew 2:9-10[4] that the star did not lead the wise men all the way from the east, otherwise why would they rejoice to see it again? Furthermore, there is a wording in Numbers 24:17 that suggests that the star did the moving. The verse says,

I shall see him, but not now: I shall behold

him, but not nigh: there shall come a Star out of Jacob, and a Sceptre

shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite the corners of Moab, and destroy all

the children of Sheth.[5]

The references to the star coming out of Jacob and the Sceptre arising out of Israel suggest that a manifestation of the star, as the angel of the Lord, is to arise out of Israel as a physical phenomenon. This would be independent of the celestial pageantry we shall shortly describe. That same star, the angel of the Lord, led the Magi to Bethlehem a year and a half later. As seen from the east, the vision of the angelic star of the Lord mentioned in connection with the wise men would likely have been seen rising in the western sky, towards Israel. Since no natural event can behave the way the star behaved, we conclude that the star of Bethlehem was the angel of the Lord.

How Did the Wise Men Recognize the Star?

Most of the Magi’s astronomical observations took place in the early morning hours, during which they would have seen the conjunction of Venus and Jupiter in August of 3 B.C. They then searched for further signs, and found them, in the triple conjunction of Jupiter with Regulus. On June 17, 2 B.C., Jupiter again joined with Venus, this time in the early evening. The Magi, observing this conjunction from Mesopotamia, would have seen this conjunction on the western horizon, precisely in the direction of Judea. Jupiter and Venus would have been visible only for a short time before setting in the western horizon.

This conjunction likely was what started the Magi to Jerusalem for the celestial pageantry they knew would end in six months, by which time the King of the Jews would certainly be born.

How, then, did the wise men know to recognize the signs of the King’s birth? The wisest man in all of Babylon was Daniel. He was great among the Chaldeans of Babylon and a chief of princes. When Babylon fell, its conqueror, Darius the Mede, named the elderly Daniel to be chief of the three princes of his government. Now Darius was a humane and wise ruler and took Babylon without bloodshed beyond the death of king Belshazzar. So it was that the Babylonians highly regarded their conqueror. The Medes, who conquered Babylon, in turn had such a high regard for the Persians that they made them co-rulers of what came to be known as the Medo-Persian Empire. In the sixth century B.C., a man named Zoroaster rose from their number and founded a religion, based on fire. The priests of the Zoroastrian religion were called Magi. Thus the Magi were to the Medes and the Persians what the Chaldeans were to the Babylonians. Zoroaster incorporated quite a bit of Judaism, thus the Magi likely knew of the prophecies of the book of Daniel and knew not only what signs to look for, but even when, as Daniel chapter nine allows the time to be computed. Thus the wise men knew to recognize the signs of the King’s birth.

Even the Romans were aware of the prophecies of Daniel and those of Balaam. Roman historians in the early second century wrote of the firm belief that had long prevailed through the East that Rome was destined to be the empire of the world until a time when someone would come forth from Judea to be king of the world. The Roman emperor Nero was advised to move his seat of empire from Rome to Jerusalem because that city was then destined to become the capital of the world. Nero declined. However, in 2 B.C. the Romans thought they already had the fulfillment of the prophecy staring at them in the face in the form of Caesar Augustus. They didn’t feel the need to look elsewhere for interpretations.

Most Jews respected the Magi of the east because they were not idolaters. Though the Magi believed that the power of the deity was manifested in the natural elements of fire, water, air, and earth, these Gentile priests did not set up material images in recognition of God.

The Arrival of the Magi

When the Magi arrived in Jerusalem and made their presence known, Herod was justifiably alarmed. His own court astrologers had no doubt given Herod their own interpretation of the celestial events of the previous months, but Herod, knowing the reputation of the Magi and the esteem in which they were held by the Jews, decided that he needed more information. Furthermore, to refuse an audience with these Magi, who had the ear and respect of eastern royalty, would have been regarded as a slight, not to mention extremely bad manners. The Sanhedrin, the Supreme Court of the Jews, was also anxious to hear what the Magi had to say.

How many Magi, or their point of origin, is not told. Persons of their stature would not have traveled by camel; they would have made the journey on horseback. So with all due respect to the makers of Christmas cards, the three kings on camels depicted on most Christmas cards has no basis in fact. The legend of the “three kings” probably arose because of the three different gifts presented to the newborn king: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Three gifts, three kings; the explanation is probably as simple as that.

Depending on their point of origin, the journey would have taken the wise men anywhere from two to four months or more, with a stopover in Jerusalem. This would have put their arrival in Bethlehem somewhere between early September and late December of 2 B.C. Furthermore, they may not have all started from the same place; they could have stopped along the way and picked up, or consulted with, more of their colleagues. Several places have been proposed for their point of origin, including Babylon, Persia, or Sheba in Arabia. Although some think there is a reference in the Old Testament of the Magi coming from Arabia, this is spurious. Most likely they were Persian. There are historical references to an incident that occurred in A.D. 614 when Persian armies invaded the Holy Land, destroying Christian churches. When the soldiers came to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, they refused to destroy it because of a mosaic depicting the adoration of the Magi. It turns out the soldiers recognized the Magi because of their dress; they were fellow Persians.

Why, if the Magi were well aware of the prophecy concerning the birth of the King of the Jews, did they stop at Jerusalem and ask Herod for directions? For one thing, as emissaries of royalty, they were bound by their own code to pay their respects to royalty in cities through which they passed. Indeed, there is a certain sense of anticipation that the king would live in a palace. Bethlehem was about six miles south of Jerusalem; once the Magi obtained this information, they were on their way, bearing gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, the traditional gifts for newborn royalty.

After departing from Herod, the star went before them and led them the six miles to Bethlehem, stopping over the very house where Mary and Joseph resided. We have earlier noted that the star was the angel of the Lord. The earliest authorities say that the wise men arrived on 25 December. At the time of the wise men’s arrival, Jesus was no longer an infant but a young child, for Matthew 2:11 states: “And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh.”

Two of the last three astronomical events in the celestial pageantry surrounding Christ’s birth also happened on 25 December. Firstly, since 27 August Jupiter had been proceeding in its usual forward or prograde motion. The prograde motion ended with Jupiter in the constellation Virgo. To the naked eye, Jupiter remained stationary for nearly six days. Secondly, the 25th was at the Winter Solstice, when the sun was also “standing still” in its yearly north-south motion, pausing at its southernmost point to reverse its direction to the north. The third and last astronomical event was the total eclipse of the moon which happened the next month, on 9 January 1 B.C.

Conclusion

We have traced the astronomical events that surrounded the birth of Jesus and how these events were interpreted in Rome and Persia. We looked at the nature of the Star of Bethlehem and concluded that its behavior at the start of the wise men’s journey, and especially at the end, could not be explained by any natural phenomenon or star. We thus concluded that the Star of Bethlehem was the Angel of the Lord and that no participant in the celestial pageantry, nor the pageantry itself, could be the Star of Bethlehem.

(Next:

Historical

Perspectives—the dating of Christ’s birth.)

[1] For a review of many of the

arguments involving the date of Christ’s birth see G. D. Bouw, 1980. “On the Star of Bethlehem,” Creation Research Society Quarterly 17(3):174-181. Also see: Bouw, G.D., 1998. “The Star of Bethlehem,” B.A. 8(86):12.

[2] Genesis 49:9-10—Judah is a

lion's whelp: from the prey, my son, thou art gone up: he stooped down,

he couched as a lion, and as an old lion; who shall rouse him

up? 10 The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor

a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come; and unto him shall the

gathering of the people be.

[3] For more on the morning star

see Bouw, G. D., 2001. “The Morning

Stars,” B. A., 11(97):69.

[4] Matthew 2:9-10—When they had

heard the king, they departed; and, lo, the star, which they saw in the east,

went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. 10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy.

[5] The reference is to Sheth,

the Egyptian god, not to the son of Adam, Seth. Sheth was the Egyptian name for the devil. The Egyptians considered him the god of

exuberant male sexuality—not channeled into fertility. He induced men to participate in pederasty

and sodomy. Sheth was also the god of

chaos and disorder, the personification of violence and bad faith. In short, Sheth is Satan.